Robin Hanson recently blogged about Futarchy again. In honor of that, here is a post I have been kicking around.

This post contains ideas related to futarchy in settings where the futarchic proposals have wide latitude to change their own goals. I originally thought of some of these ideas in the context of smart-contract based DAOs, where a "Futarchy DAO" could be given control of its own code. I am actually aware of a project to use futarchy for a DAO, but I don't know to what extent that system allows for the DAO's goals to be changed.

Mutating Preferences

Let us posit a DAO, controlled by futarchy, with the ability to control its own code. We can also posit that this futarchy starts with some utility function, a simple on-chain accessible metric of success which is the figure of merit that the futarchy is designed to maximize. Perhaps it could start out as something like "The value of the ETH balance of the core DAO smart contract on January 1st 2040".

The key observation I am making here is that, because the utility function is an aspect of the smart contract's program, the DAO can change its utility itself through proposals. This provides an interesting mechanism for cooperation between the DAO and other agents.

Suppose I have some goals I would like to use my money to advance. By virtue of its greater capital, the DAO may be able to accomplish my goals more effectively than I could on my own. I can propose a transaction to the DAO, which allows the DAO to withdraw money from my account in a one-time payoff, in exchange for the DAO modifying its own utility function adding my utility function to its own. Will the DAO accept my proposal?

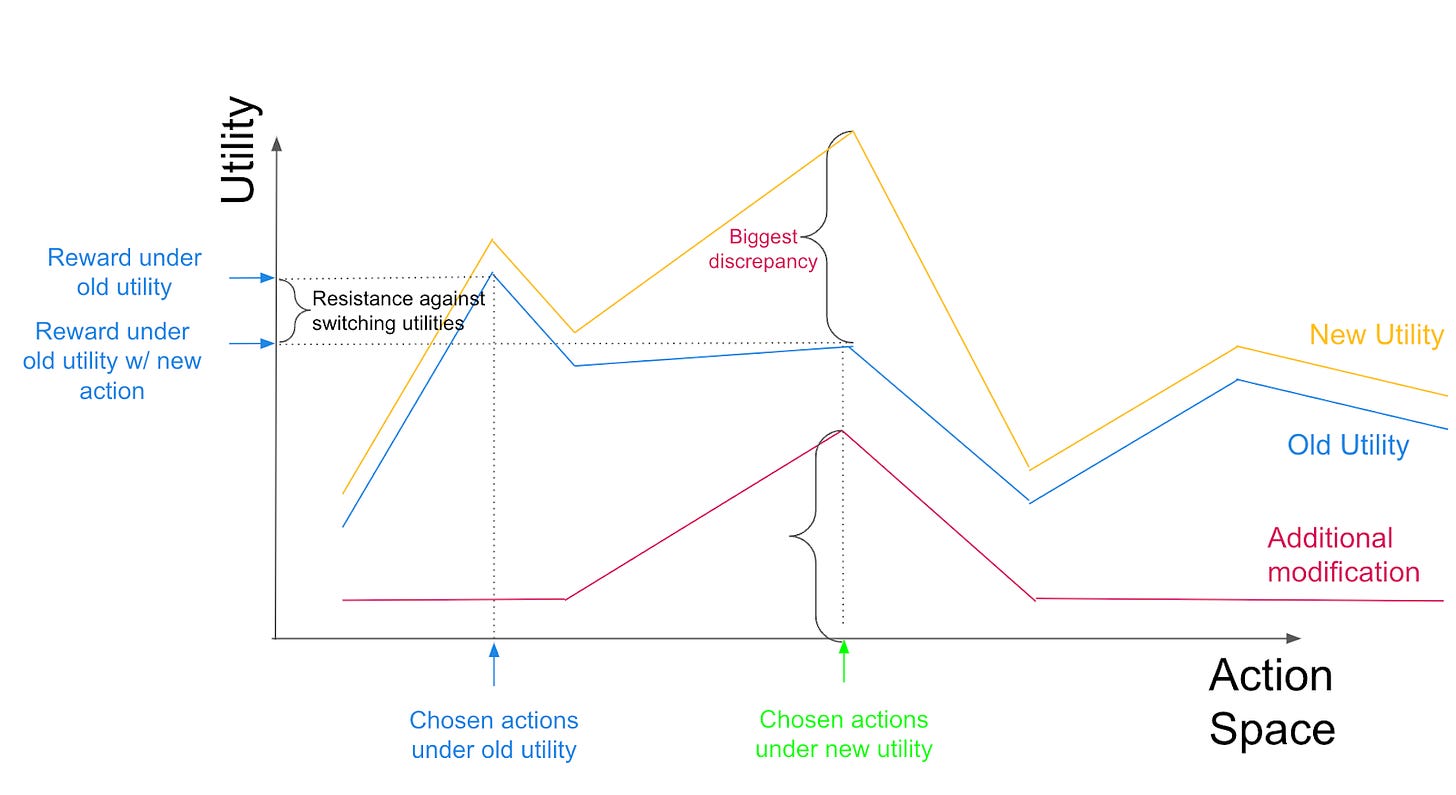

As long as the utility function of the DAO does not change uniformly by more than the amount of money I give it directly as a payoff, I claim that the answer is likely yes. Assuming that the additional money doesn't somehow restrict the space of actions the DAO can take, it will always be possible for the DAO to do whatever it would have done if its utility hadn't changed. While the DAO might end up deciding to do something different due to the utility modification, if the function we added is smaller in its maximum value than the payoff, the DAOs preference for this new action choice over the old should not be large. In particular, it should be small enough not to outweigh its preference to take the payoff, even by the lights of its old utility function.

So as long as the change in utility function is offset by the DAO's gains from the additional resources, it will profit the DAO to migrate to the new utility function. At the very least, the DAO should be willing to accept X ETH in exchange for mutating its utility by any X-bounded function. And really, if the DAO expects its actions to be largely unchanged after the update, it should be willing to accept even less.

The consequence is that if there is any service that the DAO can perform for me, I can get the DAO to perform that service by modifying its utility function to incentivize it. The price will be the amount that performing the service hurts the DAO's other objectives.

As a Bank

For example, suppose the DAO has shown an aptitude for investing, and typically generates a 10% return on its capital. My own desire is to have as much ETH as possible in one year. I can suggest a transaction that will give the DAO 1 ETH, in exchange for modifying the DAO's utility function to place 1.09 ETH worth of positive utility on the DAO sending me 1.08 ETH within a year. The DAO accepts this update because it thinks it can invest my 1 ETH to get back 1.10 ETH in a year, and it reasons that even though it will likely later be convinced to send the 1.08 ETH (since 1.09 > 1.08), it will still come out with 0.02 ETH more than it started with, and so it will have increased its own utility.

For Altruism

Suppose that I have some altruistic goal, like lowering the fraction of the world's people in poverty. Rather than donate my money to some charity to pursue this goal, I could send my money to the DAO to mutate its utility to have more of a preference for lowering poverty (as reported by some trustworthy oracle). This might be more effective than other donations because the DAO might already be aligned with the goal (because, say, others have already instilled the DAO with the goal of raising global GDP), and the DAO might be willing to accept a larger change in utility function for a smaller price.

As an explicit example, suppose I want to reduce poverty in a certain region as much as possible. I have only 75 ETH, and with that amount of capital, I can only make investments that reduce poverty by 0.75%. The DAO has a preference of 100 ETH for each 1% rise in GDP in the region. The DAO can make only one of two investments, each of which requires a large amount of capital (so I couldn't make these investments myself), and which are neutral in return. One investment funds a program which will raise GDP 1%.

The other funds a program to reduce poverty by 1% with a side effect of raising GDP by 0.5%. If I send my 75 ETH to the contract to get it to increase its utility on lowering poverty enough to take the second option, then the DAO will accept, because under its preexisting preference, it will sustain a relative loss in GDP of only 0.5%, while gaining 1 ETH. I will be happy because for the price of only 75 ETH I have decreased poverty by 1%.

Optimizing for Simplicity

A key design consideration on smart contracts is gas efficiency. But if we are considering adding components to our DAO's utility function frequently as a part of its operation, then we might worry that the ecosystem will be required to spend a lot of gas to evaluate the function. How can this be fixed?

Statistical Futarchy

One solution is "statistical futarchy".1 Suppose our utility function is determined by a smart contract that evaluates and sums thousands of different functions. We can replace this contract with one that selects at random a subset of 100 of them, and averages the values these return. Since the utility given by the new contract equals that of the old in expectation, the values of the futarchy contract shares should be roughly equivalent, and so we should not expect this change to affect the DAO's behavior.

Rewarding Golfing

Another observation is that we can reduce the gas directly by golfing the utility function. One form that this could take is annihilation of contrary goals: If the DAO has two utility components which are literally opposites of each other, they can simply both be removed. More generally, if there is some way of rewriting the function to consume less gas, a transaction can be submitted to replace the existing code. This will likely be accepted, since the DAO will have the same goals as before, but the gas costs will be less, and if these gas costs come out of the DAO's treasury, then the DAO benefits directly. This even provides an avenue for funding the software development work: the DAO can accept a proposal to golf its utility function in exchange for a payment.

Attacking the DAO through DeFi

What is to stop an individual from influencing the DAO at the margin? Consider, as an example, the utility: "The value in ETH of all the ERC-20 tokens the DAO owns, as determined by their sale price on Uniswap''. This seems like a natural metric for the DAO's wealth. But if Uniswap is very liquid, then it doesn't matter to the DAO which ERC-20 token it holds its balance in. An enterprising attacker might pay a small amount to change the utility function to "The value in ETH of all the DOGTOKEN tokens the DAO owns, as determined by their sale price on Uniswap'', causing the DAO to re-allocate its position.

This is not as concerning as it appears. Usually we would be worried that this would allow the attacker to profit by purchasing DOGTOKEN in advance, and then for the attacker to sell their own DOGTOKEN at the higher price - a classic "pump-and-dump". But in that case, the profit the attacker makes is incurred as a loss to the DAO as slippage. The DAO would hopefully be aware of this possibility, and would therefore not accept the proposal in the first place. More broadly, it would know that moving the price like this would likely cause the market to react by selling,2 and thereby reducing the value of its token.

Robustness

Any radical proposal has the potential for pitfalls. As a bonus, here are some things that might be done to make the futarchy DAO (and really any futarchy) more robust:

Elect, by some mechanism external to the futarchy, a steering committee/supreme court with veto power over proposals.

This helps the DAO avoid unethical practices, like those mentioned in footnote 2.

It also provides a stopgap for or other unforeseen problems with the mechanism.

Randomly (say with 1% frequency) reject some proposals out-of-hand.

This ensures that the futarchic markets on the status quo have a minimum likelihood of resolving, thereby encouraging liquidity.

Limit the frequency / code complexity of proposals.

This ensures that stakeholders have the bandwidth to evaluate the proposals and forecast their effect.

It also ensures that proposals will have to compete for slots. This competition can be on the basis of particularly stellar predictions for the proposal, so that only the truly great proposals are implemented.

Allow ample time between the proposal and the closing of the futarchic markets.

This ensures that stakeholders have the time to evaluate the proposals and forecast their effect. This is particularly important when a proposal takes the form of potentially malicious code, because that code needs to be audited.

Require compelling evidence that the proposal will improve the utility. For example:

Rather than require that the utility merely increase in expectation, require that it increase by a factor of at least 1.01.

Require additionally that median and upper and lower quartile values of the forecast utility increase.

Require that a minimum fraction of market participants believe the utility will increase, rather than the entire market being supported by one actor.

This actually might be related to another Hanson idea: "Statistical Democracy", the link is broken, but I interpret the title as "pick a jury at random to decide an election".

Perhaps not though. If the DAO thought that raising the price would actually cause more people to buy, then it would be easy to get it to do so. This would be tantamount to causing the DAO itself to execute a pump-and-dump scheme.

The analysis seems myopic: it treats each “bribe” as an isolated trade-off and ignores how every permanent tweak to the DAO’s utility function compounds over time. Successive preference mutations lower the expected value of all future proposals, so a forward-looking DAO should rationally reject any scheme that shifts its utility function even with a small upfront gain because it erodes long-term utility.

Am I missing something?